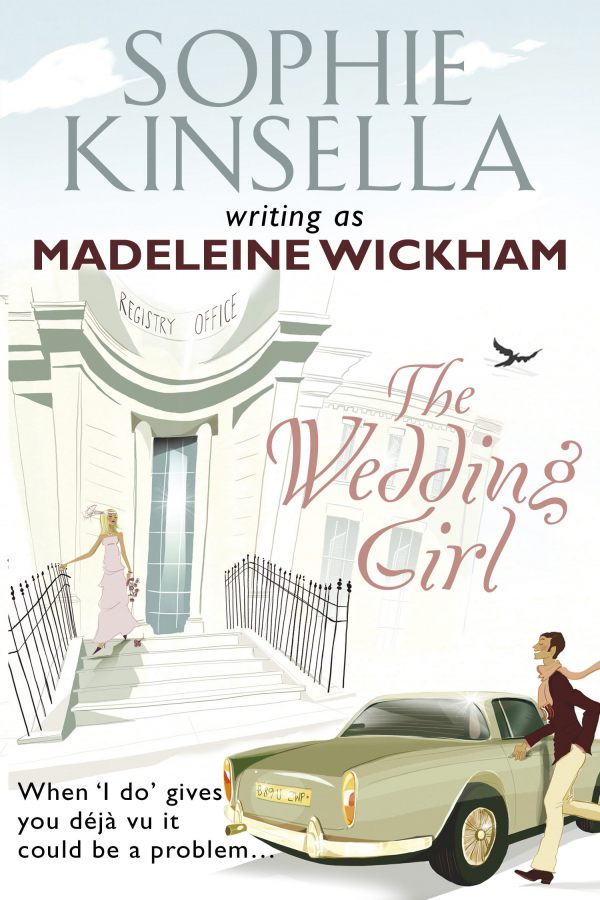

The Wedding Girl

sophie’s introduction

The Wedding Girl was the fifth book I wrote and it was tremendous fun to write. It’s about a very dizzy girl called Millie who got married in her teens to help out a friend, then sort of forgot about it. She never bothered to get a divorce and is in denial about the whole thing, which would be fine except she’s actually getting married for real in a massive prestigious wedding and suddenly her secret from the past comes out. Of course once one secret comes out, a whole load of other secrets come out… It’s a bit like dominoes! So, it’s quite a tangled up plot, it’s got a great big ticking clock and a silly heroine who’s got herself in a big pickle. It’s also set in Bath which is such a beautiful city, it was sheer pleasure to imagine my characters there.

synopsis

At the age of eighteen, in that first golden Oxford summer, Milly was up for anything. Rupert and his American lover Allan were all part of her new, exciting life, and when Rupert suggested to her that she and Allan should get married, just so that Allan could stay in the country, Milly didn’t hesitate, and to make it seem real she dressed up in cheap wedding finery and posed on the steps of the registry office for photographs.

Ten years later, Milly is a very different person. Engaged to Simon – who is wealthy, serious, and believes her to be perfect – she is facing the biggest and most elaborate wedding imaginable. Her mother has it planned to the finest detail, from the massive marquee to the sculpted ice swans filled with oysters. Her dreadful secret is locked away so securely she has almost persuaded herself that it doesn’t exist – until, with only four days to go, her past catches up with her. Suddenly, her carefully constructed world is about to crash in ruins around her. How can she tell Simon she’s already married? How can she tell her mother? But as the crisis develops, more secrets are revealed than Milly could possibly have realised…

extract

PROLOGUE

A group of tourists had stopped to gawp at Milly as she stood in her wedding dress on the registry office steps. They clogged up the pavement opposite while Oxford shoppers, accustomed to the yearly influx, stepped round them into the road, not even bothering to complain. A few glanced up towards the steps of the registry office to see what all the fuss was about, and tacitly acknowledged that the young couple on the steps did make a very striking pair.

One or two of the tourists had even brought out cameras, and Milly beamed joyously at them, revelling in their attention; trying to imagine the picture she and Allan made together. Her spiky, white-blond hair was growing hot in the afternoon sun; the hired veil was scratchy against her neck, the nylon lace on her dress felt uncomfortably damp wherever it touched her body. But still she felt light-hearted and full of a euphoric energy. And whenever she glanced up at Allan – at her husband – a new, hot thrill of excitement coursed through her body, obliterating all other sensation.

She had only arrived in Oxford three weeks ago. School had finished in July – and while all her friends had planned trips to Ibiza and Spain and Amsterdam, Milly had been packed off to a secretarial college in Oxford. ‘Much more useful than some silly holiday,’ her mother had announced firmly. ‘And just think what an advantage you’ll have over the others when it comes to job-hunting.’ But Milly didn’t want an advantage over the others. She wanted a suntan and a boyfriend, and beyond that, she didn’t really care.

So on the second day of the typing course, she’d slipped off after lunch. She’d found a cheap hairdresser and, with a surge of exhilaration, told him to chop her hair short and bleach it. Then, feeling light and happy, she’d wandered around the dry, sun-drenched streets of Oxford, dipping into cool cloisters and chapels, peering behind stone arches, wondering where she might sunbathe. It was pure coincidence that she’d eventually chosen a patch of lawn in Corpus Christi College; that Rupert’s rooms should have been directly opposite; that he and Allan should have decided to spend that afternoon doing nothing but lying on the grass, drinking Pimm’s.

She’d watched, surreptitiously, as they sauntered onto the lawn, clinked glasses and lit up cigarettes; gazed harder as one of them took off his shirt to reveal a tanned torso. She’d listened to the snatches of their conversation which wafted through the air towards her and found herself longing to know these debonair, good-looking men. When, suddenly, the older one addressed her, she felt her heart leap with excitement.

‘Have you got a light?’ His voice was dry, American, amused.

‘Yes,’ she stuttered, feeling in her pocket. ‘Yes, I have.’

‘We’re terribly lazy, I’m afraid.’ The younger man’s eyes met hers: shyer; more diffident. ‘I’ve got a lighter; just inside that window.’ He pointed to a stone mullioned arch. ‘But it’s too hot to move.’

‘We’ll repay you with a glass of Pimm’s,’ said the American. He’d held out his hand. ‘Allan.’

‘Rupert.’

She’d lolled on the grass with them for the rest of the afternoon, soaking up the sun and alcohol; flirting and giggling; making them both laugh with her descriptions of her fellow secretaries. At the pit of her stomach was a feeling of anticipation which increased as the afternoon wore on: a sexual frisson heightened by the fact that there were two of them and they were both beautiful. Rupert was lithe and golden like a young lion; his hair a shining blond halo; his teeth gleaming white against his smooth brown face. Allan’s face was crinkled and his hair was greying at the temples, but his grey-green eyes made her heart jump when they met hers, and his voice caressed her ears like silk.

When Rupert rolled over onto his back and said to the sky, ‘Shall we go for something to eat tonight?’ she’d thought he must be asking her out. An immediate, unbelieving joy had coursed through her; simul taneously she’d recognized that she would have preferred it if it had been Allan.

But then Allan rolled over too, and said ‘Sure thing.’ And then he leaned over and casually kissed Rupert on the mouth.

The strange thing was, after the initial, heart-stopping shock, Milly hadn’t really minded. In fact, this way was almost better: this way, she had the pair of them to herself. She’d gone to San Antonio’s with them that night and basked in the jealous glances of two fellow secretaries at another table. The next night they’d played jazz on an old wind-up gramophone and drunk mint juleps and taught her how to roll joints. Within a week, they’d become a regular threesome.

And then Allan had asked her to marry him.

Immediately, without thinking, she’d said yes. He’d laughed, assuming she was joking, and started on a lengthy explanation of his plight. He’d spoken of visas, of Home Office officials, of outdated systems and discrimination against gays. All the while, he’d gazed at her entreatingly, as though she still needed to be won over. But Milly was already won over, was already pulsing with the excitement at the thought of dressing up in a wedding dress, holding a bouquet; doing something more exciting than she’d ever done in her life. It was only when Allan said, half frowning, ‘I can’t believe I’m actually asking someone to break the law for me!’ that she realized quite what was going on. But the tiny qualms which began to prick her mind were no match for the exhilaration pounding through her as Allan put his arm around her and said quietly into her ear, ‘You’re an angel.’ Milly had smiled breathlessly back, and said, ‘It’s nothing,’ and truly meant it.

And now they were married. They’d hurtled through the vows: Allan in a dry, surprisingly serious voice; Milly quavering on the brink of giggles. Then they’d signed the register. Allan first, his hand quick and deft, then Milly, attempting to produce a grown-up signature for the occasion. And then, almost to Milly’s surprise, it was done, and they were husband and wife. Allan had given Milly a tiny grin and kissed her again. Her mouth still tingled slightly from the touch of him; her wedding finger still felt self-conscious in its gold-plated ring.

‘That’s enough pictures,’ said Allan suddenly. ‘We don’t want to be too conspicuous.’

‘Just a couple more,’ said Milly quickly. It had been almost impossible to persuade Allan and Rupert that she should hire a wedding dress for the occasion: now she was wearing it, she wanted to prolong the moment for ever. She moved slightly closer to Allan, clinging to his elbow, feeling the roughness of his suit against her bare arm. A sharp summer breeze had begun to ripple through her hair, tugging at her veil and cooling the back of her neck. An old theatre programme was being blown along the dry empty gutter; on the other side of the street the tourists were starting to melt away.

‘Rupert!’ called Allan. ‘That’s enough snapping!’

‘Wait!’ said Milly desperately. ‘What about the confetti!’

‘Well, OK,’ said Allan indulgently. ‘I guess we can’t forget Milly’s confetti.’

He reached into his pocket and tossed a multi-coloured handful into the air. At the same time, a gust of wind caught Milly’s veil again, this time ripping it away from the tiny plastic tiara in her hair and sending it spectacularly up into the air like a gauzy plume of smoke. It landed on the pavement, at the feet of a dark-haired boy of about sixteen, who bent and picked it up. He began to look at it carefully, as though examining some strange artefact.

‘Hi’ called Milly at once. ‘That’s mine!’ And she began running down the steps towards him, leaving a trail of confetti as she went. ‘That’s mine,’ she repeated clearly as she neared the boy, thinking he might be a foreign student; that he might not understand English.

‘Yes,’ said the boy, in a dry, well-bred voice. ‘I gathered that.’

He held out the veil to her and Milly smiled self- consciously at him, prepared to flirt a little. But the boy’s expression didn’t change; behind the glint of his round spectacles, she detected a slight teenage scorn. She felt suddenly aggrieved a little foolish, standing bare-headed, in her ill-fitting nylon wedding dress.

‘Thanks,’ she said, taking the veil from him. The boy shrugged.

‘Any time.’

He watched as she fixed the layers of netting back in place, her hands self-conscious under his gaze. ‘Congratulations,’ he added.

‘What for?’ said Milly, without thinking. Then she looked up and blushed. ‘Oh yes, of course. Thank you very much.’

‘Have a happy marriage,’ said the boy in deadpan tones. He nodded at her and before Milly could say anything else, walked off.

‘Who was that?’ said Allan, appearing suddenly at her side.

‘I don’t know,’ said Milly. ‘He wished us a happy marriage.’

‘A happy divorce, more like,’ said Rupert, who was clutching Allan’s hand. Milly looked at him. His face was glowing; he seemed more beautiful than ever before.

‘Milly, I’m very grateful to you,’ said Allan. ‘We both are.’

‘There’s no need to be,’ said Milly. ‘Honestly, it was fun!’

‘Well, even so. We’ve bought you a little something.’ Allan glanced at Rupert, then reached in his pocket and gave Milly a little box. ‘Freshwater pearls,’ he explained as she opened it. ‘We hope you like them.’

‘I love them!’ Milly looked from one to the other, eyes shining. ‘You shouldn’t have!’

‘We wanted to,’ said Allan seriously. ‘To say thank you for being a great friend – and a perfect bride.’ He fastened the necklace around Milly’s neck, and she flushed with pleasure. ‘You look beautiful,’ he said softly. ‘The most beautiful wife a man could hope for.’

‘And now,’ said Rupert, ‘how about some champagne?’

They spent the rest of that day punting down the Cherwell, drinking vintage champagne and making extravagant toasts to each other. In the following days, Milly spent every spare moment with Rupert and Allan. At the weekends they drove out into the countryside, laying sumptuous picnics out on checked rugs. They visited Blenheim, and Milly insisted on signing the visitors’ book, Mr and Mrs Allan Kepinski. When, three weeks later, her time at secretarial college was up, Allan and Rupert reserved a farewell table at the Randolph, made her order three courses and wouldn’t let her see the prices.

The next day, Allan took her to the station, helped her stash her luggage on a rack, and dried her tears with a silk handkerchief. He kissed her goodbye, and promised to write and said they would meet in London soon.

Milly never saw him again.

ONE

TEN YEARS LATER

The room was large and airy and overlooked the biscuity streets of Bath, coated in a January icing of snow. It had been refurbished some years back in a traditional manner, with striped wallpaper and a few good Georgian pieces. These, however, were currently lost under the welter of bright clothes, CDs, magazines and make-up piled high on every available surface. In the corner a handsome mahogany wardrobe was almost entirely masked by a huge white cotton dress carrier; on the bureau was a hat box; on the floor by the bed was a suitcase half full of clothes for a warm-weather honeymoon.

Milly, who had come up some time earlier to finish packing, leaned back comfortably in her bedroom chair, glanced at the clock, and took a bite of toffee apple. In her lap was a glossy magazine, open at the problem pages. ‘Dear Anne,’ the first began. ‘I have been keeping a secret from my husband.’ Milly rolled her eyes. She didn’t even have to look at the advice. It was always the same. Tell the truth. Be honest. Like some sort of secular catechism, to be learned by rote and repeated without thought.

Her eyes flicked to the second problem. ‘Dear Anne. I earn much more money than my boyfriend.’ Milly crunched disparagingly on her toffee apple. Some problem. She turned over the page to the homestyle section, and peered at an array of expensive waste-paper baskets. She hadn’t put a waste-paper basket on her wedding list. Maybe it wasn’t too late.

Downstairs, there was a ring at the doorbell, but she didn’t move. It couldn’t be Simon, not yet; it would be one of the bed and breakfast guests. Idly, Milly raised her eyes from her magazine and looked around her bedroom. It had been hers for twenty-two years, ever since the Havill family had first moved into 1 Bertram Street and she had unsuccessfully petitioned, with a six-year-old’s desperation, for it to be painted Barbie pink. Since then, she’d gone away to school, gone away to college, even moved briefly to London – and each time she’d come back again; back to this room. But on Saturday she would be leaving and never coming back. She would be setting up her own home. Starting afresh. As a grown-up, bona fide, married woman.

‘Milly?’ Her mother’s voice interrupted her thoughts, and Milly’s head jerked up. ‘Simon’s here!’

‘What?’ Milly glanced in the mirror and winced at her dishevelled appearance. ‘He can’t be.’

‘Shall I send him up?’ Her mother’s head appeared round the door and surveyed the room. ‘Milly! You were supposed to be clearing this lot up!’

‘Don’t let him come up,’ said Milly, looking at the toffee apple in her hand. ‘Tell him I’m trying my dress on. Say I’ll be down in a minute.’

Her mother disappeared, and Milly quickly threw her toffee apple into the bin. She closed her magazine and put it on the floor, then, on second thoughts, kicked it under the bed. Hurriedly she peeled off the denim-blue leggings she’d been wearing and opened her wardrobe. A pair of well-cut black trousers hung to one side, along with a charcoal grey tailored skirt, a chocolate trouser suit and an array of crisp white shirts. On the other side of the wardrobe were all the clothes she wore when she wasn’t going to be seeing Simon: tattered jeans, ancient jerseys, tight bright miniskirts. All the clothes she would have to throw out before Saturday.

She put on the black trousers and one of the white shirts, and reached for the cashmere sweater Simon had given her as a Christmas present. She looked at herself severely in the mirror, brushed her hair – now buttery blond and shoulder-length – till it shone, and stepped into a pair of expensive black loafers. She and Simon had often agreed that buying cheap shoes was a false economy; as far as Simon was aware, her entire collection of shoes consisted of the black loafers, a pair of brown boots, and a pair of navy Gucci snaffles which he’d bought for her himself.

Sighing, Milly closed her wardrobe door, stepped over a pile of underwear on the floor, and picked up her bag. She sprayed herself with scent, closed the bedroom door firmly behind her and began to walk down the stairs.

‘Milly!’ As she passed her mother’s bedroom door, a hissed voice drew her attention. ‘Come in here!’

Obediently, Milly went into her mother’s room. Olivia Havill was standing by the chest of drawers, her jewellery box open.

‘Darling,’ she said brightly, ‘why don’t you borrow my pearls for this afternoon?’ She held up a double pearl choker with a diamond clasp. ‘They’d look lovely against that jumper!’

‘Mummy, we’re only meeting the vicar,’ said Milly. ‘It’s not that important. I don’t need to wear pearls.’

‘Of course it’s important!’ retorted Olivia. ‘You must take this seriously, Milly. You only make your marriage vows once!’ She paused. ‘And besides, all upper-class brides wear pearls.’ She held the necklace up to Milly’s throat. ‘Proper pearls. Not those silly little things.’

‘I like my freshwater pearls,’ said Milly defensively. ‘And I’m not upper class.’

‘Darling, you’re about to become Mrs Simon Pinnacle.’

‘Simon isn’t upper class!’

‘Don’t be silly,’ said Olivia crisply. ‘Of course he is. His father’s a multimillionaire.’ Milly rolled her eyes.

‘I’ve got to go,’ she said.

‘All right.’ Olivia put the pearls regretfully back into her jewellery box. ‘Have it your own way. And, darling, do remember to ask Canon Lytton about the rose petals.’

‘I will,’ said Milly. ‘See you later.’

She hurried down the stairs and into the hall, grabbing her coat from the hall stand by the door.

‘Hi!’ she called into the drawing room, and as Simon came out into the hall, glanced hastily at the front page of that day’s Daily Telegraph, trying to commit as many headlines as possible to memory.

‘Milly,’ said Simon, grinning at her. ‘You look gorgeous.’ Milly looked up and smiled.

‘So do you.’ Simon was dressed for the office, in a dark suit which sat impeccably on his firm, stocky frame, a blue shirt and a purple silk tie. His dark hair sprang up energetically from his wide forehead and he smelt discreetly of aftershave.

‘So,’ he said, opening the front door and ushering her out into the crisp afternoon air. ‘Off we go to learn how to be married.’

‘I know,’ said Milly. ‘Isn’t it weird?’

‘Complete waste of time,’ said Simon. ‘What can a crumbling old vicar tell us about being married? He isn’t even married himself.’

‘Oh well,’ said Milly vaguely. ‘I suppose it’s the rules.’

‘He’d better not start patronizing us. That will piss me off.’

Milly glanced at Simon. His neck was tense and his eyes fixed determinedly ahead. He reminded her of a young bulldog ready for a scrap.

‘I know what I want from marriage,’ he said, frowning. ‘We both do. We don’t need interference from some stranger.’

‘We’ll just listen and nod,’ said Milly. ‘And then we’ll go.’ She felt in her pocket for her gloves. ‘Anyway, I already know what he’s going to say.’

‘What?’

‘Be kind to one another and don’t sleep around.’ Simon thought for a moment.

‘I expect I could manage the first part.’

Milly gave him a thump and he laughed, drawing her near and planting a kiss on her shiny hair. As they neared the corner he reached in his pocket and bleeped his car open.

‘I could hardly find a parking space,’ he said, as he started the engine. ‘The streets are so bloody congested.’ He frowned. ‘Whether this new bill will really achieve anything…’

‘The environment bill,’ said Milly at once.

‘That’s right,’ said Simon. ‘Did you read about it today?’

‘Oh yes,’ said Milly. She cast her mind quickly back to the Daily Telegraph. ‘Do you think they’ve got the emphasis quite right?’

And as Simon began to talk, she looked out of the window and nodded occasionally, and wondered idly whether she should buy a third bikini for her honeymoon.

Canon Lytton’s drawing room was large, draughty and full of books. Books lined the walls, books covered every surface, and teetered in dusty piles on the floor. In addition, nearly everything in the room that wasn’t a book, looked like a book. The teapot was shaped like a book, the firescreen was decorated with books; even the slabs of gingerbread sitting on the tea-tray resembled a set of encyclopaedia volumes.

Canon Lytton himself resembled a sheet of old paper. His thin, powdery skin seemed in danger of tearing at any moment; whenever he laughed or frowned his face creased into a thousand lines. At the moment – as he had been during most of the session – he was frowning. His bushy white eyebrows were knitted together, his eyes narrowed in concentration and his bony hand, clutched around an undrunk cup of tea, was waving dangerously about in the air.

‘The secret of a successful marriage,’ he was declaiming, ‘is trust. Trust is the key. Trust is the rock.’

‘Absolutely,’ said Milly, as she had at intervals of three minutes for the past hour. She glanced at Simon. He was leaning forward, as though ready to interrupt. But Canon Lytton was not the sort of speaker to brook interruptions. Each time Simon had taken a breath to say something, the clergyman had raised the volume of his voice and turned away, leaving Simon stranded in frustrated but deferential silence. He would have liked to take issue with much of what Canon Lytton was saying, she could tell. As for herself, she hadn’t listened to a word.

Her gaze slid idly over to the glass-fronted bookcase to her left. There she was, reflected in the glass. Smart and shiny; grown-up and groomed. She felt pleased with her appearance. Not that Canon Lytton appreciated it. He probably thought it was sinful to spend money on clothes. He would tell her she should have given it to the poor instead.

She shifted her position slightly on the sofa, stifled a yawn, and looked up. To her horror, Canon Lytton was watching her. His eyes narrowed, and he broke off mid-sentence.

‘I’m sorry if I’m boring you, my dear,’ he said sarcastically. ‘Perhaps you are familiar with this quotation already.’

Milly felt her cheeks turn pink.

‘No,’ she said, ‘I’m not. I was just… um…’ She glanced quickly at Simon, who grinned back and gave her a tiny wink. ‘I’m just a little tired,’ she ended feebly.

‘Poorly Milly’s been frantic over the wedding arrangements,’ put in Simon. ‘There’s a lot to organize. The champagne, the cake…’

‘Indeed,’ said Canon Lytton severely. ‘But might I remind you that the point of a wedding is not the champagne, nor the cake; nor is it the presents you will no doubt receive.’ His eyes flicked around the room, as though comparing his own dingy things with the shiny, sumptuous gifts piled high for Milly and Simon, and his frown deepened. ‘I am grieved,’ he continued, stalking over to the window, ‘at the casual approach taken by many young couples to the wedding ceremony. The sacrament of marriage should not be viewed as a formality.’

‘Of course not,’ said Milly.

‘It is not simply the preamble to a good party.’

‘No,’ said Milly.

‘As the very words of the service remind us, marriage must not be undertaken carelessly, lightly, or selfishly, but—’

‘And it won’t be!’ Simon’s voice broke in impatiently; he leaned forward in his seat. ‘Canon Lytton, I know you probably come across people every day who are getting married for the wrong reasons. But that’s not us, OK? We love each other and we want to spend the rest of our lives together. And for us, that’s a serious matter. The cake and the champagne have got nothing to do with it.’

He broke off and for a moment there was silence. Milly took Simon’s hand and squeezed it.

‘I see,’ said Canon Lytton eventually. ‘Well, I’m glad to hear it.’ He sat down, took a sip of cold tea and winced. ‘I don’t mean to lecture you unduly,’ he said, putting down his cup. ‘But you’ve no idea how many un suitable couples I see coming before me to get married. Thoughtless young people who’ve barely known each other five minutes; silly girls who want an excuse to buy a nice dress…’

‘I’m sure you do,’ said Simon. ‘But Milly and I are the real thing. We’re going to take it seriously. We’re going to get it right. We know each other and we love each other and we’re going to be very happy.’ He leaned over and kissed Milly gently, then looked up at Canon Lytton, as though daring him to reply.

‘Yes,’ said Canon Lytton. ‘Well. Perhaps I’ve said enough. You do seem to be on the right track.’ He picked up his folder and began to rifle through it. ‘There are just a couple of other matters…’

‘That was beautiful,’ whispered Milly to Simon.

‘It was true,’ he whispered back, and gently touched the corner of her mouth.

‘Ah yes,’ said Canon Lytton, looking up. ‘I should have mentioned this before. As you will be aware. Reverend Harries neglected to read your banns last Sunday.’

‘Did he?’ said Simon.

‘Surely you noticed?’ said Canon Lytton looking beadily at Simon. ‘I take it you were at morning service?’

‘Oh yes,’ said Simon after a pause. ‘Of course. Now you mention it, I thought something was wrong.’

‘He was most apologetic – they always are.’ Canon Lytton gave a tetchy sigh. ‘But the damage has been done. So you will have to be married by special licence.’

‘Oh,’ said Milly. ‘What does that mean?’

‘It means, among other things,’ said Canon Lytton, ‘that I must ask you to swear an oath.’

‘Zounds damnation,’ said Milly.

‘I’m sorry?’ He looked at her in puzzlement.

‘Nothing,’ she said. ‘Carry on.’

‘You must swear a solemn oath that all the infor mation you’ve given me is true,’ said Canon Lytton. He held out a bible to Milly, then passed her a piece of paper. ‘Just run your eyes down it, check that it’s all correct, then read the oath aloud.’

Milly stared down at the paper for a few seconds, then looked up with a bright smile.

‘Absolutely fine,’ she said.

‘Melissa Grace Havill,’ said Simon, reading over her shoulder. ‘Spinster.’ He pulled a face. ‘Spinster!’

‘OK!’ said Milly sharply. ‘Just let me read the oath.’

‘That’s right,’ said Canon Lytton. He beamed at her. ‘And then everything will be, as they say, above board.’

By the time they emerged from the vicarage, the air was cold and dusky. Snowflakes were falling again; the street lamps were already on; a row of fairy lights from Christmas twinkled in a window opposite. Milly took a deep breath, shook out her legs, stiff from sitting still for so long, and looked at Simon. But before she could speak, a triumphant voice came ringing from the other side of the street.

‘Aha! I just caught you!’

‘Mummy!’ exclaimed Milly.

‘Olivia,’ said Simon. ‘What a lovely surprise.’

Olivia crossed the street and beamed at them both. Snowflakes were resting lightly on her smartly cut blond hair and on the shoulders of her green cashmere coat. Nearly all of Olivia’s clothes were in jewel colours – sapphire blue, ruby red, amethyst purple – accented by shiny gold buckles, gleaming buttons and gilt-trimmed shoes. She had once secretly toyed with the idea of turquoise-tinted contact lenses but had been unable to reassure herself that she wouldn’t become the subject of smirks behind her back. And so instead she made the most of her natural blue by pasting a bright gold on her eyelids and visiting a beautician once a month to have her lashes dyed black.

Now her eyes were fixed affectionately on Milly.

‘I don’t suppose you asked Canon Lytton about the rose petals, did you?’ she said.

‘Oh!’ said Milly. ‘No, I forgot.’

‘I knew you would!’ exclaimed Olivia. ‘So I thought I’d better pop round myself.’ She smiled at Simon. ‘Isn’t my little girl a scatterhead?’

‘I wouldn’t say so,’ said Simon in a tight voice.

‘Of course you wouldn’t! You’re in love with her!’ Olivia smiled gaily at him and ruffled his hair. In high heels she was very slightly taller than Simon, and he’d noticed – though nobody else had – that since he and Milly had become engaged, Olivia wore high heels more and more frequently.

‘I’d better be going,’ he said. ‘I’ve got to get back to the office. We’re frantic at the moment.’

‘Aren’t we all!’ exclaimed Olivia. ‘There are only four days to go, you know! Four days until you walk down that aisle! And I’ve a thousand things to do!’ She looked at Milly. ‘What about you, darling? Are you rushing off?’

‘Not me,’ said Milly. ‘I took the afternoon off.’

‘Well then, how about walking back into town with me? Perhaps we could have…’

‘Hot chocolate at Mario’s,’ finished Milly.

‘Exactly.’ Olivia smiled almost triumphantly at Simon. ‘I can read Milly’s mind like an open book!’

‘Or an open letter,’ said Simon. There was a short, tense pause.

‘Right, well,’ said Olivia eventually, in clipped tones. ‘I won’t be long. See you this evening, Simon.’ She opened Canon Lytton’s gate and began to walk quickly up the path, skidding slightly on the snow.

‘You shouldn’t have said that,’ said Milly to Simon, as soon as she was out of earshot. ‘About the letter. She made me promise not to tell you.’

‘Well, I’m sorry,’ said Simon. ‘Milly, you must be joking. It was addressed to you and it was in your bedroom!’

‘Oh well,’ said Milly good-naturedly. ‘It doesn’t really matter.’ She gave a sudden giggle. ‘It’s a good thing you didn’t write anything rude about her.’

‘Next time I will,’ said Simon. He glanced at his watch. ‘Look, I’ve really got to go.’

He took hold of her chilly fingers, kissed them gently one by one, then pulled her towards him. His mouth was soft and warm on hers; as he drew her gradually closer to him, Milly closed her eyes. Then, suddenly he let go of her, and a blast of cold snowy air hit her in the face.

‘I must run. See you later.’

‘Yes,’ said Milly. ‘See you then.’

She watched, smiling to herself, as he bleeped open the door of his car, got in and, without pausing, zoomed off down the street. Simon was always in a hurry. Always rushing off to do; to achieve. Like a puppy, he had to be out every day, either doing something constructive or determinedly enjoying himself. He couldn’t bear wasting time; didn’t understand how Milly could spend a day happily doing nothing, or approach a weekend with no plans made. Sometimes he would join her in a day of drifting indolence, repeating several times that it was nice to have a chance to relax. Then, after a few hours, he would leap up and announce he was going for a run.

The first time she’d ever seen him, in someone else’s kitchen, he’d been simultaneously conducting a conversation on his mobile phone, shovelling crisps into his mouth, and bleeping through the news headlines on Teletext. As Milly had poured herself a glass of wine, he’d held his glass out too and, in a gap in his conversation, had grinned at her and said, ‘Thanks.’

‘The party’s happening in the other room,’ Milly had pointed out.

‘I know,’ Simon had said, his eyes back on the Teletext. ‘I’ll be along in a minute.’ And Milly had rolled her eyes and left him to it, not even bothering to ask his name. But later on that evening, when he’d rejoined the party, he’d come up to her, introduced himself charmingly, and apologized for having been so distracted.

‘It was just a bit of business news I was particularly interested in,’ he’d said.

‘Good news or bad news?’ Milly had enquired, taking a gulp of wine and realizing that she was rather drunk.

‘That depends,’ said Simon, ‘on who you are.’

‘But doesn’t everything? Every piece of good news is someone else’s bad news. Even…’ She’d waved her glass vaguely in the air. ‘Even world peace. Bad news for arms manufacturers.’

‘Yes,’ Simon had said slowly. ‘I suppose so. I’d never thought of it like that.’

‘Well, we can’t all be great thinkers,’ Milly had said, and had suppressed a desire to giggle.

‘Can I get you a drink?’ he’d asked.

‘Not a drink,’ she’d replied. ‘But you can light me a cigarette if you like.’

He’d leaned towards her, cradling the flame carefully, and she’d registered that his skin was smooth and tanned, and his fingers strong, and he was wearing an aftershave she liked. Then, as she’d inhaled on the cigarette, his dark brown eyes had locked into hers, and to her surprise a tingle had run down her back, and she’d slowly smiled back at him.

Later on, when the party had turned from bright, stand-up chatter into groups of people sitting on the floor and smoking joints, the discussion had turned to vivisection. Milly, who had happened to see a Blue Peter special on vivisection the week before while at home with a cold, had produced more hard facts and informed reasoning than anyone else, and Simon had gazed at her in admiration.

He’d asked her out to dinner a few days later and talked a lot about business and politics. Milly, who knew nothing about either subject, had smiled and nodded and agreed with him; at the end of the evening, just before he kissed her for the first time, Simon had told her she was extraordinarily perceptive and understanding. When, a bit later on, she’d tried to tell him that she was woefully ignorant on the subject of politics – indeed, on most subjects – he’d chided her for being modest. ‘I saw you at that party,’ he’d said, ‘destroying that guy’s puerile arguments. You knew exactly what you were talking about. In fact,’ he’d added, with darkening eyes, ‘it was quite a turn-on.’ And Milly, who’d been about to admit to her source of infor mation, had instead moved closer so that he could kiss her again.

Simon’s initial impression of her had never been corrected. He still told her she was too modest; he still thought she liked the same highbrow art exhibitions he did; he still asked her opinion on topics such as the American presidency campaign and listened carefully to her answers. He thought she liked sushi; he thought she had read Sartre. Without wanting to mislead him, but without wanting to disappoint him either, she’d allowed him to build up a picture of her which – if she were honest with herself – wasn’t quite true.

Quite what was going to happen when they started living together, she didn’t know. Sometimes she felt alarmed at the degree to which she was being mis represented; felt sure she would be exposed as a fraud the first time he caught her crying over a trashy novel. At other times, she told herself that his picture of her wasn’t so inaccurate. Perhaps she wasn’t quite the sophisticated woman he thought she was – but she could be. She would be. It was simply a matter of discarding all her old clothes and wearing only the new ones. Making the odd intelligent comment – and staying discreetly quiet the rest of the time.

Once, in the early days of their relationship, as they lay together in Simon’s huge double bed at Pinnacle Hall, Simon had told her that he’d known she was someone special when she didn’t start asking him questions about his father. ‘Most girls’ he’d said bitterly, ‘just want to know what it’s like, being the son of Harry Pinnacle. Or they want me to get them a job interview or something. But you . . . you’ve never even mentioned him.’

He’d gazed at her with incredulous eyes, and Milly had smiled sweetly and murmured an indistinct, sleepy response. She could hardly admit that the reason she’d never mentioned Harry Pinnacle was that she’d never heard of him.

’So – dinner with Harry Pinnacle tonight! That should be fun.’ Her mother’s voice interrupted Milly’s thoughts, and she looked up.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I suppose so.’

‘Has he still got that wonderful Austrian chef?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Milly. She had, she realized, begun to imitate Simon’s discouraging tone when talking about Harry Pinnacle. Simon never prolonged a conversation about his father if he could help it; if people were too persistent he would change the subject abruptly, or even walk away. He had walked away from his future mother-in-law plenty of times as she pressed him for details and anecdotes about the great man. So far she had never seemed to notice.

‘The really lovely thing about Harry,’ mused Olivia, ‘is that he’s so normal.’ She tucked Milly’s arm cosily under her own and they began to walk down the snowy street together. ‘That’s what I say to everybody. If you met him, you wouldn’t think, here’s a multimillionaire tycoon. You wouldn’t think, here’s a founder of a huge national chain. You’d think, what a charming man. And Simon’s just the same.’

‘Simon isn’t a multimillionaire tycoon,’ said Milly. ‘He’s an ordinary advertising salesman.’

‘Hardly ordinary, darling!’

‘Mummy…’

‘I know you don’t like me saying it. But the fact is that Simon’s going to be very wealthy one day.’ Olivia’s arm tightened slightly around Milly’s. ‘And so are you.’ Milly shrugged.

‘Maybe.’

‘There’s no point pretending it’s not going to happen. And when it does, your life will change.’

‘No it won’t.’

‘The rich live differently, you know.’

‘A minute ago,’ pointed out Milly, ‘you were saying how normal Harry is. He doesn’t live differently, does he?’

‘It’s all relative, darling.’

They were nearing a little parade of expensive boutiques; as they approached the first softly lit window, they both stopped. Inside the window was a single mannequin, exquisite in heavy white velvet.

‘That’s nice,’ murmured Milly.

‘Not as nice as yours,’ said Olivia at once. ‘I haven’t seen a single wedding dress as nice as yours.’

‘No,’ said Milly slowly. ‘Mine is nice, isn’t it?’

‘It’s perfect, darling.’

They lingered a little at the window, sucked in by the rosy glow of the shop; the clouds of silk, satin and netting lining each wall; the dried bouquets and tiny embroidered bridesmaids’ shoes. At last Olivia sighed.

‘All this wedding preparation has been fun, hasn’t it? I’ll be sorry when it’s all over.’

‘Mmm,’ said Milly. There was a little pause, then Olivia said, as though changing the subject, ‘Has Isobel got a boyfriend at the moment?’

Milly’s head jerked up.

‘Mummy! You’re not trying to marry Isobel off, too.’

‘Of course not! I’m just curious. She never tells me anything. I asked if she wanted to bring somebody to the reception . . .’

‘And what did she say?’

‘She said no,’ said Olivia regretfully.

‘Well then.’

‘But that doesn’t prove anything.’

‘Mummy,’ said Milly. ‘If you want to know if Isobel’s got a boyfriend, why don’t you ask her?’

‘Maybe,’ said Olivia in a distant voice, as though she wasn’t really interested any more. ‘Yes, maybe I will.’

An hour later they emerged from Mario’s Coffee House, and headed for home. By the time they got back, the kitchen would be filling up with bed and breakfast guests, footsore from sightseeing. The Havills’ house in Bertram Street was one of the most popular bed and breakfast houses in Bath: tourists loved the beautifully furnished Georgian townhouse; its proximity to the city centre; Olivia’s charming, gossipy manner and ability to turn every gathering into a party.

Tea was always the busiest meal in the house; Olivia adored assembling her guests round the table for Earl Grey and Bath buns. She would introduce them to one another, hear about their day, recommend diversions for the evening and tell them the latest gossip about people they had never met. If any guest expressed a desire to retreat to his own room and his mini-kettle, he was given a look of disapproval and cold toast in the morning. Olivia Havill despised mini-kettles and tea-bags on trays; she only provided them in order to qualify for four rosettes in the Heritage City Bed and Breakfast Guide. Similarly she despised, but provided, cable television, vegetarian sausages and a rack of leaflets about local theme parks and family attractions – which, she was glad to note, rarely needed replenishing.

‘I forgot to say,’ said Olivia, as they turned into Bertram Street. ‘The photographer arrived while you were out. Quite a young chap.’ She began to root around in her handbag for the doorkey.

‘I thought he was coming tomorrow.’

‘So did I!’ said Olivia. ‘Luckily those nice Australians have had a death in the family, otherwise we wouldn’t have had room. And speaking of Australians . . . look at this!’ She put her key in the front door and swung it open.

‘Flowers!’ exclaimed Milly. On the hall stand was a huge bouquet of creamy white flowers, tied with a dark green silk ribbon bow. ‘For me? Who are they from?’

‘Read the card,’ said Olivia. Milly picked up the bouquet and reached inside the cracking plastic.

‘“To dear little Milly,”’ she read slowly. ‘“We’re so proud of you and only wish we could be there at your wedding. We’ll certainly be thinking of you. With all our love from Beth, Scott and Adrian.”’ Milly looked at Olivia in amazement.

‘Isn’t that sweet of them! All the way from Sydney. People are so kind.’

‘They’re excited for you, darling,’ said Olivia. ‘Everyone’s excited. It’s going to be such a wonderful wedding!’

‘Why, aren’t those pretty,’ came a pleasant voice from above. One of the bed and breakfast guests, a middle-aged woman in blue slacks and sneakers, was coming down the stairs. ‘Flowers for the bride?’

‘Just the first,’ said Olivia, with a little laugh.

‘You’re a lucky girl,’ said the middle-aged woman to Milly.

‘I know I am,’ said Milly and a pleased grin spread over her face. ‘I’ll just put them in some water.’

Still holding her flowers, Milly pushed open the door to the kitchen, then stopped in surprise. Sitting at the table was a young man wearing a shabby denim jacket. He had dark brown hair and round metal spectacles and was reading the Guardian.

‘Hello,’ she said politely. ‘You must be the photographer.’

‘Hi there,’ said the young man, closing his paper. ‘Are you Milly?’

He looked up, and as she saw his face, Milly felt a jolt of recognition. Surely she’d met this guy before somewhere?

‘I’m Alexander Gilbert,’ he said in a dry voice, and held out his hand. Milly advanced politely and shook it.

‘Nice flowers,’ he said, nodding to her bouquet.

‘Yes,’ replied Milly, staring curiously at him. Where on earth had she seen him before? Why did his face feel etched in her memory?

‘That’s not your wedding bouquet, though.’

‘No, it’s not,’ said Milly. She bent her head slightly and inhaled the sweet scent of the flowers. ‘These were sent by some friends in Australia. It’s really thoughtful of them, considering—’

Suddenly she broke off, and her heart began to beat faster.

‘Considering what?’ said Alexander.

‘Nothing,’ said Milly, backing away. ‘I mean – I’ll just go and put them away.’

She moved towards the door, her palms sweaty against the crackling plastic. She knew where she’d seen him before. She knew exactly where she’d seen him before. At the thought of it, her heart gave a terrified lurch and she gritted her teeth, forcing herself to stay calm. Everything’s OK, she told herself as she reached for the door handle. Everything’s OK. As long as he doesn’t recognize me…

‘Wait.’ His voice cut across her thoughts as though he could read her mind. Feeling suddenly sick, she turned round, to see him staring at her with a slight frown. ‘Wait a minute,’ he said. ‘Don’t I know you?’

audio extract

goodreads reviews

media reviews

"Gutsy prose and an excellent ear for social comedy."

The Independent