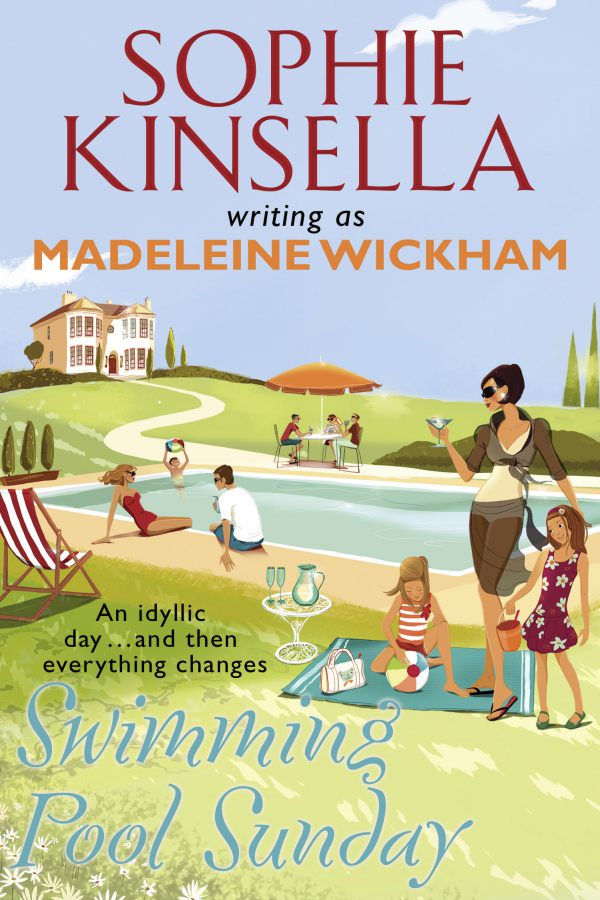

Swimming Pool Sunday

sophie’s introduction

I think of all the books I’ve ever written, Swimming Pool Sunday is the darkest, and is probably the least like my Sophie Kinsella books. In fact, it’s quite a serious drama with some big issues. It starts off in an idyllic way, in a country village by a swimming pool. All the families are splashing in the pool, it’s a lovely gorgeous sunny day and everyone is having a lot of fun. Then there’s an accident and a child gets hurt, which results in a lawsuit which splits the community in two, and it all gets quite painful and messy.

I wrote it several years ago when litigation was all quite new, but since then, it’s come further and further into our lives so it still feels like a very relevant issue.

synopsis

On a shimmeringly hot Sunday in May, the Delaneys opened their pool to all the village for charity. Louise was there, so were her daughters Amelia and Katie – and so, glaring at her resentfully, was her estranged husband Barnaby. This was supposed to be his day with the girls. But Louise ignored his angry glowers – it wasn’t her fault they’d wanted to come swimming with her, was it? Whilst the children splashed and shrieked in the cool, blue waters, she lay blissfully back in the sun and dreamed of Cassian, the charismatic new lawyer in her life. The day seemed perfect.

But suddenly the perfect day was shattered, as tragedy struck. And the consequences of a terrible accident developed into a drama of recriminations, jealousy and legal power-play, in which Louise found herself pulled in three directions all at once. Friendships crumbled, the village was split, and the needs of a child became secondary to the dangerous contest in which the grown-ups were engaged.

extract

ONE

It was only May, and it was only ten o’clock in the morning. But already the sun was shining hotly, and the grass in the garden sprang warm and dry underfoot, and the breeze under Katie’s cotton dress felt friendly and caressing. Katie gave a little wriggle. She felt like doing some ballet jumps, or rolling down the slope of the lawn until she landed in a heap at the bottom. But instead she had to stand, still as a rock, with elastic round her legs stretched so tightly it was going to give her red marks. She bent down and shifted the elastic slightly.

‘Katie!’ Amelia, who had been about to jump, stopped, and regarded her crossly. ‘You mustn’t move!’

‘It hurts! It’s too tight!’ Katie bent her head round until she could catch a glimpse of the backs of her calves. She spotted a small pink line. ‘Look! It’s making marks on my skin!’

’Well, stand nearer the chair, then. But keep the elastic tight.’ Katie gave a melodramatic sigh and shuffled nearer the chair.

They were playing with a chair because you needed three people for French skipping, and there were only two of them. Sometimes Mummy played with them, but today she was too busy, and had got cross when they asked. So they’d had to drag a chair out into the garden, and thread the elastic round its legs, just like human legs. Now it stretched, two white springy lines, a few inches above the grass. The very sight of it filled Katie with an excited anticipation. She loved French skipping. They played it in every single break at school; during lessons she would often put her hand into her pocket and check that the tangled mass of elastic was still safely there.

‘Right.’ Amelia sounded businesslike. She began to jump efficiently over the taut elastic, biting her lip, and planting her feet carefully in exactly the right places. ‘Jingle, jangle, centre, spangle,’ she chanted. ‘Jingle, jangle, out.’ She jumped out without even touching the elastic.

‘My go,’ said Katie hopefully.

‘No it isn’t,’ retorted Amelia. ‘Don’t you know how to play French skipping?’

‘In my class,’ said Katie, raising her eyebrows expressively, ‘we play so that everybody has one go, and then it’s the next person. Mrs Tully said that’s the fairest way.’ Amelia wasn’t impressed.

‘That’s just for little ones,’ she said. ‘We play until the person makes a mistake.’

‘But you’ll never make a mistake!’ cried Katie. She scratched the place on her leg where the elastic had been too tight.

‘Yes I will, I expect,’ said Amelia kindly. ‘And anyway,’ she added, ‘at least you know it’s your turn next; I don’t think the chair will want to play.’ Katie looked at the chair, standing benignly on the grass. She giggled.

‘We could ask it,’ she began. But Amelia had started jumping again.

‘Jingle, jangle, centre, spangle, jingle, jangle, out.’

They had been sent out to play in the garden until their father came to pick them up. Nobody could quite remember what time he’d said he was coming. Amelia thought it was ten, and their mother thought it was tenthirty, and Katie had been convinced it was quarter to nine, like school, and had actually stood by the door, ready to go, until nine o’clock had come and gone and it was obvious he was coming later.

Amelia had suggested, sensibly, that Mummy should ring Daddy and ask him. But for some reason she didn’t want to. She never wanted to ring Daddy. It was always Daddy who rang. He’d rung during the week, and talked to Mummy, and said he was going to take the girls fishing this Sunday. Fishing! Katie had never even been fishing. They’d both got very excited and gone down into the cellar and brought up all the nets and buckets they could find. Amelia actually had a fishing-rod that Grandfather had given her, and she’d generously said that Katie could hold it with her if she wanted. Mummy had washed out two jamjars for them, in case there was anything small that they wanted to bring home, and they’d chosen a chocolate bar each as a special treat for their packed lunch.

But all of them, even Mummy, had forgotten that this Sunday was Swimming Day at the Delaneys’ house. They couldn’t miss the Swimming Day. Everyone was going from the village; even people who didn’t really like swimming. Amelia briefly wondered what it must be like, to be a person who didn’t like swimming. She simply couldn’t imagine it. Everyone she knew liked swimming: her, Katie, Mummy, even Daddy when he was really hot.

They’d only remembered about the Swimming Day yesterday, when they bumped into Mrs Delaney at the shops, and she asked if they were coming, and Mummy said that she thought this year, unfortunately, the girls would have to miss it. Katie had nearly started crying right there in the street. Amelia was more grown up than that, but as soon as they were in the car, she’d asked in a desperate voice, ‘Couldn’t we go to the Swimming Day tomorrow and go fishing another time?’ At first Mummy had said no, of course not, in an angry voice. Then, when they got home, she’d said no, but it really was a pity. Then, later, she’d said maybe Daddy wouldn’t mind. And last night, as she tucked them into bed, she’d said that as soon as Daddy arrived, she would ask him, and she thought he was sure to agree.

‘Jingle, jangle, out.’ Amelia thumped heavily onto the grass. ‘I’m boiling,’ she added.

‘So’m I,’ said Katie quickly. ‘I can’t wait to go swimming.’

‘I’m going to dive straight in,’ said Amelia. ‘I’m not even going to feel it with my toe or anything.’

‘So’m I,’ said Katie again. ‘I’m going to dive in.’

‘You can’t dive,’ said Amelia crushingly.

‘I can,’ retorted Katie. ‘I learned it in swimming. You sit on the side and…’

‘That’s not a proper dive.’

‘It is!’

‘It isn’t.’

‘It is!’ Katie’s voice rose in fury. ‘It is a proper dive!’ Amelia smirked silently. ‘I did it the best in my class,’ shrilled Katie. ‘Mrs Tully said I was a little otter.’

There was a pause. Then Amelia wrinkled her nose superciliously and said, ‘Yuck.’

‘What?’ Katie looked discomfited. ‘Why is it yuck?’

‘Being an otter is yuck.’ Amelia looked at Katie challengingly, and Katie met Amelia’s gaze silently for a moment, then she looked away. Amelia’s eyes glinted.

‘You don’t know what an otter is, do you?’ she said.

‘Yes, I do!’

‘What is it, then?’

Katie stared crossly at Amelia. Her mind scrambled over half-imagined pictures. Had Mrs Tully ever actually told her what an otter was? Otter. What did it sound like? Into her mind came an image of blue-green water; of silvery streaks of light and a lithe body shooting through the water in a perfect dive.

‘It’s like a flower fairy,’ she said eventually. ‘It’s a water fairy. It lives in the water and it’s all blue and green.’

Amelia started to crow. ‘No, it’s not! Katie Kember, you don’t know anything!’

‘Well, what is it then?’ shouted Katie angrily. Amelia brought her face up close to Katie’s.

‘It’s an animal. It’s all slithery and hairy and its feet are all webbed and slimy. That’s what you are. You thought you were a water fairy!’

Katie sat down on the grass. It didn’t occur to her not to believe Amelia. Amelia hardly ever made things up.

‘I haven’t got slimy feet,’ she said, her voice trembling slightly, ‘and I’m not all hairy; I’ve just got normal hair.’ She pushed her bright brown fringe off her forehead and looked at Amelia with worried blue eyes. Amelia relented.

‘No, but otters are really good at swimming,’ she said. ‘I expect that’s what Mrs Tully meant.’

‘Yes, that’s what she meant,’ said Katie, immensely cheered. ‘I’m the best swimmer in my class, you know. Some of them still have arm-bands.’

‘One boy in my class still has arm-bands,’ said Amelia, giggling, ‘and he’s nine.’

‘Nine!’ echoed Katie scornfully. She was only just seven, and she’d been swimming without arm-bands since last summer.

Suddenly there was the sound of a car pulling ,up outside the house.

‘Daddy!’

‘Daddy!’

They both ran around the side of the house. There was their father getting out of the car, as tall as ever, wearing a pair of shorts and a very old-looking blue checked shirt. There was a combination of familiarity and strangeness about the sight of him which made Amelia stop momentarily in her tracks and look away. Katie pushed past her.

‘Daddy!’ she cried. Their father turned and smiled. And immediately, predictably, Katie burst into noisy. copious tears.

Louise Kember sat in her pretty kitchen and waited for Barnaby to come in. She’d heard the car pull up, heard the girls run out to greet him, and could now hear Katie’s muffled sobs. It was nearly five months since Barnaby had moved out, and still Katie wept every time he arrived or left. And every time, a hand seemed to squeeze Louise’s heart until fresh painful guilt filled her chest.

Hadn’t she been told that it was far better for parents to separate than to stay together, arguing? In those awful few weeks over Christmas, when the rows between her and Barnaby had reached their height, when her frustrations and his suspicions had spilled over into everything they did, contaminating every gesture and giving every seemingly innocuous remark a double-edged meaning, she’d been convinced that when the split did come, it would be a relief for all of them. For her and Barnaby, certainly, but also for the girls.

Larch Tree Cottage wasn’t big enough for two shouting parents and two sleeping children; more than once she and Barnaby had been interrupted mid-flow by a white-faced, white-nightied little person at the kitchen door. They would shoot accusing looks at one another as they quickly adopted soothing voices, proffered glasses of water and spoke gaily to Mr Teddy or Mrs Rabbit. And then they would inevitably both go back upstairs with whichever of the girls it was, in a self- conscious togetherness – tucking in and tiptoeing out as though they were once again the young married couple besotted with their first baby.

For a few moments the pretence would last. They would float down the stairs together in a cloud of deliberate good nature, fulfilling the image of the happy, loving, contented parents. But downstairs in the kitchen, the air would be thick with lingering, remembered jibes. The smiles would fade. Barnaby would mutter something incomprehensible about popping to The George for a quick half, and Louise would run a hot bath and weep frustratedly into the foamy water. By the time Barnaby got back she would be in bed, sometimes pretending to be asleep, sometimes sitting up, having formulated in her mind exactly what she wanted to say. But Barnaby would wave her speeches aside.

‘I’m too tired, Lou,’ he’d say. ‘Busy day tomorrow. Can’t it wait?’

‘No, my life can’t wait,’ she once hissed back. ‘It’s been on hold for ten years already.’ But Barnaby was already in his automatic, unseeing, unthinking, undressing and going-to-bed mode, and he didn’t even reply. Louise stared at him in exasperated anger.

‘Listen to me!’ she screeched, forgetting the children, forgetting everything but her need to communicate. ‘If you really loved me you’d listen to me!’ And Barnaby looked up, baffled.

‘I do love you,’ he said in a low resentful voice, folding up his trousers. ‘You know I love you.’ And then he stopped and looked away.

And Louise looked away too. Because the truth was that she did know that Barnaby loved her. But knowing that Barnaby loved her was no longer enough.

Katie was sitting on the grassy bank outside the cottage next to Barnaby. His arm was round her, and she was juddering slightly, but her tears had dried up. On the other side of Barnaby was Amelia, who felt a bit like crying herself, but was far too grown up.

‘That’s better,’ said Barnaby. He squeezed them both tightly so their faces were squashed against his shirt. After a moment Katie started to wriggle.

‘I can’t breathe,’ she gasped dramatically. Amelia said nothing. She felt safe, all squashed up against Daddy, smelling his smell and hearing his laugh. Of course, Mummy hugged them all the time, but it wasn’t the same. It wasn’t so… cosy. Her face was pressed up against a shirt button and her neck was a bit twisted, but still she could have stayed safely inside Daddy’s hug all morning.

But Barnaby was letting go of them and reaching into the car.

‘Here you are, you two,’ he said, tossing a package into each lap. ‘Vital equipment for the day.’ The two girls began to unwrap their parcels and Barnaby watched, a pleased smile on his face. He’d bought each of them a present. For Katie he’d bought a small collapsible fishing-rod, and for Amelia, who already had a fishing-rod, he’d bought a smart little fishing-tackle box.

Katie unwrapped hers first. She squealed in delight and leaped up.

‘Goody gum drops! A real fishing-rod! You can keep your smelly old rod, Amelia!’

But Amelia looked up from her tackle box in sudden realization, and said in dismay, ‘What about going swimming?’

‘What about it?’ said Barnaby easily. ‘I’m afraid you’ll have to leave that to the fish. You might be able to paddle, though.’

‘No, silly!’ Katie dropped her fishing-rod on the ground and rushed over to Barnaby. ‘Swimming Day, at Mrs Delaney’s house! Can we go instead of fishing?’

Barnaby tried to hide his surprise.

‘What! Don’t you want to go fishing?’

‘I want to go swimming,’ said Katie coaxingly. ‘It’s so hot!’

By way of illustration she began to fan her legs with the skirt of her dress. It was a familiar-looking pink and white striped dress; a cast-off of Amelia’s, Barnaby abruptly realized. He had a sudden memory of a small Amelia wearing it, leaving for a birthday party, excitedly clutching a present, while an even smaller Katie jealously watched from the stairs.

‘Mummy said you wouldn’t mind,’ offered Amelia. She tried to signal to Katie to shut up. She would make Daddy cross if she wasn’t careful, and then they’d never be allowed to go swimming. ‘We could go fishing next week,’ she suggested. Abruptly, she remembered. ‘And thank you for the lovely present,’ she added.

‘Yes, thank you, Daddy,’ said Katie quickly. She picked up her fishing-rod and stroked it tenderly. ‘For my lovely fishing-rod.’ She looked up. ‘But can we go swimming? Please? Please?’

‘I don’t know yet,’ said Barnaby, trying to keep his temper. ‘I’ll go and talk to Mummy.’

Louise had begun rather self-consciously to make some coffee, waiting for the moment when Barnaby would come in. She moved gracefully around the kitchen, a careless half smile on her lips, noting with pleasure the pretty citrus-tree stencils which she had carefully painted onto the pine back door the week before. Those, and the new curtains, splashed brightly with orange and yellow flowers, had really lifted the kitchen, she thought to herself. Next she intended to stencil the bannisters, and maybe even the sitting-room. Larch Tree Cottage had, in the ten years they’d lived there, always been pretty, in a predictable old-fashioned sort of way, but Louise was now determined to transform it into something different and beautiful; something which people would look at with admiration.

As she heard Barnaby’s heavy tread in the hallway, she glanced quickly around, as though to reaffirm in her mind the image which she presented. A happy, fulfilled, independent woman, at home in her own beautiful kitchen.

Nevertheless, she turned away as he got nearer, and turned on the coffee-grinder. Her hand trembled slightly as she pressed the top down, and the electrical shriek meant that she couldn’t hear his greeting.

‘Louise!’ As she released the pressure on the coffee-grinder and the noise died down, Barnaby’s voice sounded aggressively loud. Louise slowly turned. A jerk of fearful emotion rose up inside her, then almost immediately subsided.

‘Hello, Barnaby,’ she said in carefully modulated tones.

‘What’s all this nonsense about going swimming?’

As he heard his own rough voice, Barnaby knew he was playing this wrong; rushing in angrily instead of asking reasonably, but suddenly he felt very hurt. He’d planned this fishing expedition carefully; he’d been looking forward to it ever since he’d had the idea. The cheerful disregard with which his daughters had abandoned the idea wasn’t their fault – they were only kids; but Louise should have been more thoughtful. An angry resentment grew inside him as he looked at her, half turned away, feathery blond fronds of hair masking her expression. Was she trying to sabotage his only time with the girls? Was she turning them against him? A raw emotional wound, deep inside him, began to throb. His breathing quickened.

Louise’s head whipped round. She took in Barnaby’s accusing expression and flushed slightly.

‘It’s not nonsense,’ she said, allowing her voice to rise slightly. ‘They want to go to the Delaneys’ to swim.’ She paused. ‘I don’t blame them. It’s going to be a boiling hot day.’

She tipped ground coffee from the grinder into a cafeti8Fre and poured on hot water. A delicious smell filled the kitchen.

‘Mummy!’ Katie’s piercing voice came in from the hall. ‘Can we have a drink?’ There was the sound of sandals clattering against floorboards, and suddenly the girls were in the kitchen.

‘I’ll pour them some Ribena,’ said Barnaby.

‘Actually,’ said Louise, ‘we don’t have Ribena any more.’ Barnaby stopped still, hand reaching towards the cupboard. ‘Water will do,’ added Louise.

‘What’s wrong with Ribena?’ demanded Barnaby. He flashed a quick encouraging grin at Amelia.

‘What’s wrong with Ribena?’ Amelia echoed.

‘It’s bad for your teeth,’ said Louise firmly, ignoring Barnaby. ‘You know that.’

‘What’s wrong with Ribena?’ Amelia repeated, lolling against a kitchen cupboard.

‘I want Ri-bee-na,’ said Katie.

‘I can’t blame them,’ said Barnaby.

‘Or Tango,’ said Katie, encouraged. ‘Or Sprite. I love Sprite…’

‘All right!’ Louise shouted. There was a sudden silence. Louise scrabbled inside a jar on the work-surface.

‘Go on, both of you, along to Mrs Potter’s shop, and buy yourself a fizzy drink.’ Katie and Amelia stared at her uncertainly. ‘Go on,’ repeated Louise. Her voice trembled slightly. ‘Since it’s such a hot day. As a treat. Stay on the grassy path and come straight back.’

‘And then will we go swimming?’ said Katie.

‘Maybe,’ said Louise. She handed some coins to Amelia. ‘It depends what Daddy says.’

When they’d gone, there was silence. Louise slowly pushed down the plunger of the cafeti8Fre, lips tight. She stared down into its gleaming chrome surface for a minute, formulating words. Then she looked up.

‘I would appreciate it, Barnaby,’ she said deliberately, ‘if you would try not to undermine everything I do.’

‘I don’t!’ retorted Barnaby angrily. ‘I wasn’t to know you’d suddenly taken against Ribena. How the hell was I supposed to know?’ There was a pause. Louise poured the steaming coffee into mugs.

‘And anyway,’ added Barnaby, remembering, with a sudden resentful surge, the reason for his anger, ‘I’d appreciate it if you didn’t muscle in on my time with the girls.’

‘I’m not! How can you say that? They’re the ones who want to go swimming, not me!’

‘What, so you aren’t going swimming?’

‘I probably will go, as a matter of fact,’ said Louise, ‘but I wasn’t planning to take them.’

‘Planning to take someone else, were you?’ said Barnaby, with a sudden sneer. ‘I wonder who?’ Louise flushed.

‘That’s unfair, Barnaby.’

‘It’s perfectly fair!’ Barnaby’s voice was getting louder and louder. ‘If you want to go swimming with lover boy, then I don’t want to get in your way.’

Louise’s eyes swivelled, before she could stop them, towards a new shiny photograph, freshly pinned up on the notice-board behind the door. Barnaby’s gaze followed. His heart gave an unpleasant thud. The picture was of Louise, smiling, standing next to an elegant young man with smooth brown skin and glossy dark hair, on the steps of some grand-looking building that Barnaby didn’t recognize. They were both in evening dress; Louise wore a silky blue dress that Barnaby had never seen before. The man wore a double-breasted dinner jacket; his patent-leather dress shoes were impeccably polished and his hair had a confident well-groomed sheen. As he stared, unable to move his eyes away, Barnaby’s chest grew heavy with despair and loathing. He scanned the picture bitterly, as though searching for details, for clues; trying not to notice the excited happy look in Louise’s face as she stood, with a strange man, in a strange place. smiling for a strange photographer.

Abruptly, he turned to Louise. ‘You’ve had your hair cut.’

Louise, who had been expecting something more aggressive than that, looked surprised.

‘Yes,’ she said. Her hand moved up to her neck. ‘Do you like it?’

‘It makes you look… sexy.’

Barnaby sounded so gloomy that Louise smiled, in spite of herself.

‘Isn’t that good? Don’t you like me looking sexy?’ She was moving on to dangerous ground, but Barnaby didn’t take the bait. He was staring at her with miserable blue eyes.

‘You look like someone else’s idea of sexy, not mine.’

Louise didn’t know what to say. She took a sip of coffee. Barnaby slumped in his chair as though in sudden defeat.

For a few minutes they sat still, in almost com panionable silence. Louise’s thoughts gradually loosened themselves from the current situation and began to float idly around her mind like dust particles in the sunshine, bouncing quickly away whenever she inadvertently hit on anything too painful or serious. Sitting, sipping her coffee, feeling the sunshine warm on her face, she could almost forget about everything else. Meanwhile Barnaby sat, in spite of himself, blackly imagining Louise in a pair of strong dinner-jacketed arms; dancing, whirling, laughing, being happy, how could she?

Suddenly there was a rattling at the back door. Louise looked up. Katie was beaming in through the kitchen window, triumphantly clutching a shiny can. The door opened and Amelia bounded in.

‘We had a lift,’ she said breathlessly, ‘from Mrs Seddon-Wilson. She said, were we going to the swimming?’

‘And we said, yes we were, nearly,’ said Katie. She danced over to Barnaby. ‘Are we going, Daddy? Are we going swimming?’

‘We haven’t talked about it yet,’ said Louise quickly.

‘You must have!’ said Katie in astonishment. ‘You were talking all that time, when we went to the shop and got our drinks… They didn’t have any Sprite,’ she added sorrowfully, ‘but I got Fanta.’ She offered her can to Louise.

‘May you open my drink for me?’

‘In a minute,’ said Louise, distractedly.

‘Are we going swimming, Mummy?’ asked Amelia anxiously. ‘Mrs Seddon-Wilson said it was going to be tremendous fun.’

‘Tremendous fun,’ echoed Katie, ‘and I told her about my new swimming-suit and she said it sounded lovely.’

‘What about it, Barnaby?’ Louise adopted a brisk businesslike voice. ‘Can they go swimming?’ Barnaby looked up. His face was pink.

‘I think the girls and I should go fishing as planned,’ he said stoutly. He looked at Katie. ‘Come on, Katkin. Don’t you want to use your new rod?’

‘Yes, I do,’ said Katie simply. ‘I want to go fishing, but I want to go swimming, too.’

‘But you go swimming every week at school,’ said Barnaby, trying not to sound hectoring.

‘I know we do, Daddy,’ said Amelia, in an attempt to mollify, ‘but this swimming is different. It’s the Swimming Day. It only happens once a year.’

‘Well, tell you what,’ said Barnaby, giving her a wide smile. ‘I’ll speak to Hugh, and get him to invite us over to swim another day; just us. How about that?’ Amelia looked down and swung her foot.

‘It won’t be the same,’ she said in barely audible tones. Barnaby’s good humour snapped.

‘Why not?’ he suddenly bellowed. ‘Why is it so important that you go swimming today? What’s wrong with the lot of you?’ Louise’s eyes flashed.

‘There’s nothing wrong with the girls,’ she said icily, ‘just because they want to spend a nice hot day swimming with their friends.’ She put a proprietorial hand on Amelia’s shoulder. Amelia looked at the floor. Suddenly Katie gave a sob.

‘I’ll go fishing, Daddy! I’ll go fishing with you! Where’s my rod?’ She fumbled with the back door and rushed out into the garden.

‘Oh great,’ said Louise curtly. ‘Well, if you want to blackmail them into going with you, that’s fine.’

‘How dare you!’ Barnaby drew an angry breath. His cheeks had flushed dark red, and his forehead had begun to glisten. ‘It’s nothing to do with blackmail. Katie wants to come fishing. So would Amelia, if you hadn’t…’

‘If I hadn’t what?’ Louise’s grip tightened on Amelia’s shoulder. ‘If I hadn’t what, Barnaby?’

Barnaby looked at the two of them, mother and daughter, and suddenly a defeated look came into his eyes. ‘Nothing,’ he muttered.

Then the back door opened and Katie was in the kitchen again. She was holding her rod in one hand and a piece of tangled elastic in the other. ‘I nearly couldn’t find my French skipping,’ she said breathlessly.

‘Are you sure you want to go fishing?’ said Louise, ignoring Barnaby’s glance.

‘Yes, I’m quite sure,’ said Katie grandly. ‘And anyway, I’ve got my swimming-suit on under my dress, so I can go swimming with the little fishes.’ Barnaby began to say something, then stopped.

‘All right,’ said Louise. ‘Well, we’ll see you later, then.’ She looked at Barnaby. ‘Not too late.’

Barnaby looked at Amelia. He gave her a friendly smile.

‘How about you, Amelia? Want to come fishing?’

Amelia blushed. She looked up at Louise, then back at Barnaby.

‘Not really,’ she said in a small voice. ‘I want to go swimming. Do you mind, Daddy?’ Barnaby’s cheerful expression barely faltered.

‘Well,’ he said slowly, ‘of course I’d love you to come with us, but not if you’d rather go swimming instead. You should just do what you enjoy the most.’

‘I enjoy fishing the most,’ announced Katie, brandishing her rod. ‘I hate nasty old swimming.’

‘You love swimming,’ objected Louise.

‘Not any more,’ retorted Katie. She looked up at Barnaby. ‘Me and Daddy hate swimming, don’t we, Daddy?’ Louise’s lips tightened.

‘Well, Katie,’ she said, ‘you’re a big girl now, you can make your own decision. I just hope you don’t regret it.’

‘What’s regret?’ asked Katie immediately.

‘It’s to look back on something you’ve done,’ said Barnaby, ‘and wish you hadn’t done it. You won’t do that, will you, Katkin?’ But Katie wasn’t listening. She had begun to do her birdcage dance around the kitchen, using the fishing-rod instead of her birdcage. As she danced, she began to hum the tune.

‘We won’t regret going swimming,’ said Amelia bravely. ‘Will we, Mummy?’

‘No,’ said Louise, ‘I shouldn’t think we will. Katie, stop dancing, and go with Daddy.’ Katie stopped, foot still pointed out.

‘I don’t regret going fishing,’ she said.

‘You haven’t been yet,’ pointed out Amelia.

‘So what?’ said Katie, rudely.

‘Come on,’ said Barnaby, impatiently. ‘Go and get in the car, Katie.’ He grinned briefly at Amelia. ‘I’ll see you this evening,’ he said, ‘and we’ll tell each other about our day.’

When he had left the kitchen, Amelia’s chin began to wobble. She suddenly felt very unsure of herself. The kitchen seemed empty and silent now that Daddy and Katie had gone, and she wasn’t sure that she’d made the right decision. She looked up at Mummy for a comforting glance, but Mummy was staring at something on the notice-board. Amelia followed her gaze. It was a photograph of Mummy and Cassian.

‘Is Cassian coming swimming, Mummy?’ she asked, falteringly. Louise’s head whipped round.

‘No!’ she said. Then, at the sight of Amelia’s anxious face, her voice softened. ‘No,’ she repeated. ‘he’s in London.’

‘Oh.’ Amelia wasn’t quite sure why, but this piece of news made her feel a bit better about going swimming with Mummy instead of fishing with Daddy. ‘Oh,’ she said again. Louise suddenly smiled.

‘So we’ll have a lovely day, just the two of us,’ she said, ‘swimming and getting brown. Mummy and Amelia. What do you think?’

Into Amelia’s mind appeared a blissful image of a blue swimming-pool glittering in the sunlight, herself floating effortlessly in the middle of it. She looked happily up at Louise.

‘I think, yes please,’ she said.

‘Well, go and get your things, then,’ said Louise brightly. ‘We want to make all we can out of the day.’

Amelia clattered out of the kitchen and thudded up the narrow cottage stairs. And Louise followed at a more leisurely pace, humming gaily to herself and wondering which sun-hat she should take with her, and trying as hard as she could to dispel from her mind the lingering image of Barnaby’s indignant, angry, wounded face.

audio extract

goodreads reviews

media reviews

"A fine entertainment."

The Times