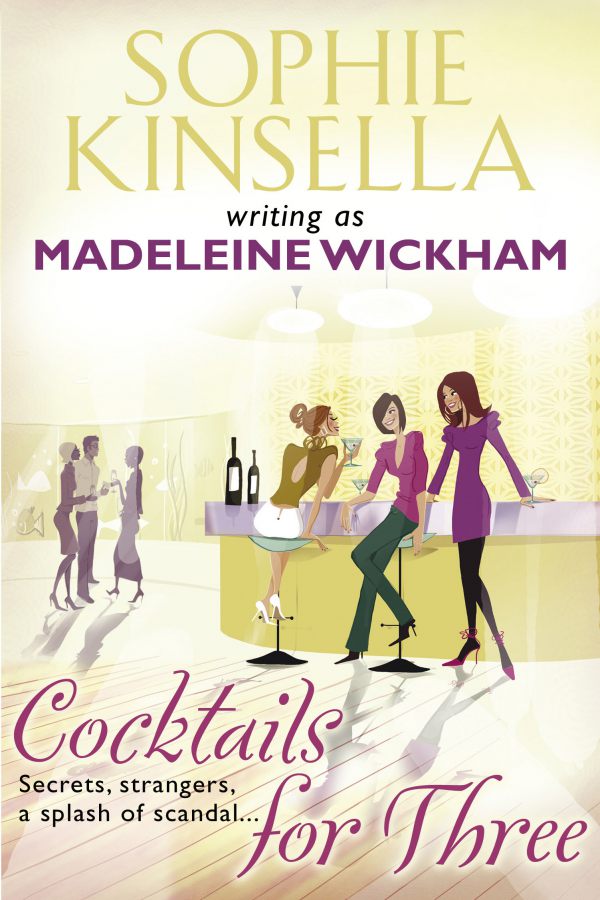

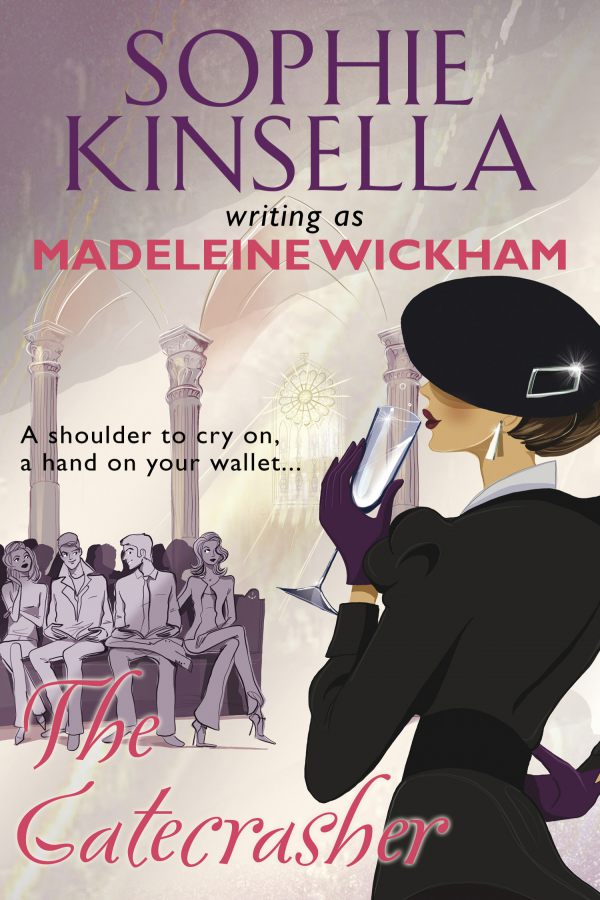

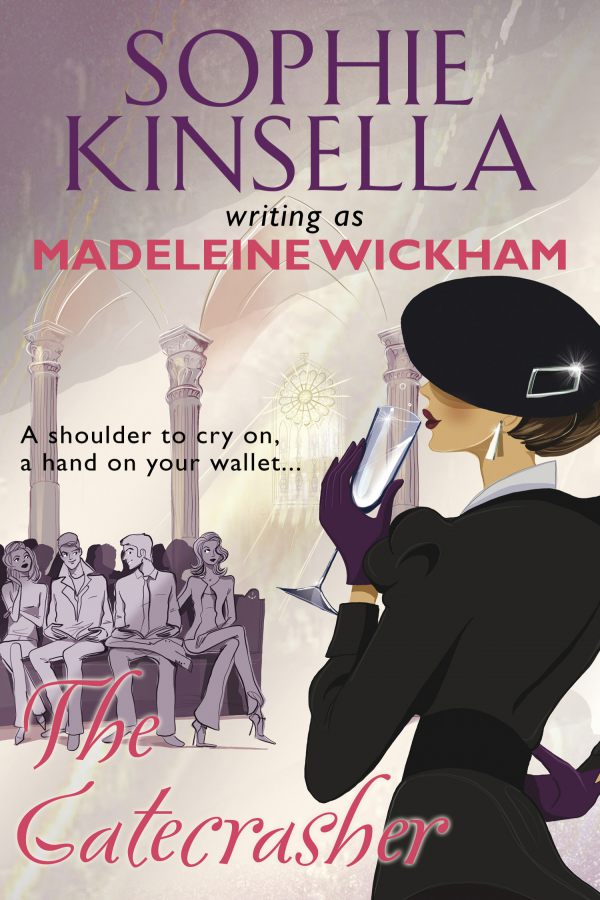

The Gatecrasher

sophie’s introduction

This book features one of my favourite heroines, Fleur Daxeny. It’s called The Gatecrasher because Fleur gatecrashes funerals and memorial services. She dresses up in black, finds services of wealthy families then goes along and infiltrates herself into the family and ultimately fleeces them. Not very much, just enough to keep herself going. So she’s not a good person – she’s beautiful and unscrupulous and she’s a user – but she’s also very warm and very witty and very life-enhancing, and you find yourself rooting for her even though you know you shouldn’t.

Fleur becomes entangled with one particular family and faces the biggest decision – does she hang up her collection of black hats and find love and settle down, or does she fleece them as usual and move on? The reaction I’ve always had from readers is that they didn’t want to like Fleur – they felt morally shocked by what she did – but by the end they kind of loved her. She’s perhaps my ultimate flawed heroine.

synopsis

Fleur is beautiful but lazy and, at forty, spends her life looking for rich men who can provide her and her teenage daughter with a glamorous and effortless existence. A daily trawl through the court pages of The Times provides her with an unusual but fertile search area – the funerals and memorial services of the great and good, where gatecrashers are so much less noticeable than they would be at a wedding or a christening.

It is at one of these sad but oddly festive occasions that she meets Richard, dull but well-off, whose mousey wife has died after a lifetime of enjoyable ill-health.

Before long Fleur has become an integral part of Richard’s life, offending his friends, interfering in his leisure pursuits (golf bores her, so why should he spend so much time on it?) and stirring up his grown-up children to behave badly.

extract

ONE

Fleur Daxeny wrinkled her nose. She bit her lip, and put her head on one side, and gazed at her reflection silently for a few seconds. Then she gave a gurgle of laughter.

‘I still can’t decide,’ she exclaimed. ‘They’re all fabulous.’

The saleswoman from Take Hat! exchanged weary glances with the nervous young hairdresser sitting on a gilt stool in the corner. The hairdresser had arrived at Fleur’s hotel suite half an hour ago and had been waiting to start ever since. The saleswoman was meanwhile beginning to wonder whether she was wasting her time completely.

‘I love this one with the veil,’ said Fleur suddenly, reaching for a tiny creation of black satin and wispy netting. ‘Isn’t it elegant?’

‘Very elegant,’ said the saleswoman. She hurried forward just in time to catch a black silk topper which Fleur was discarding onto the floor.

‘Very,’ echoed the hairdresser in the corner. Surreptitiously he glanced at his watch. He was supposed to be back down in the salon in forty minutes. Trevor wouldn’t be pleased. Perhaps he should phone down to explain the situation. Perhaps…

‘All right!’ said Fleur. ‘I’ve decided.’ She pushed up the veil and beamed around the room. ‘I’m going to wear this one today.’

‘A very wise choice, madam,’ said the saleswoman in relieved tones. ‘It’s a lovely hat.’

‘Lovely,’ whispered the hairdresser.

‘So if you could just pack the other five into boxes for me…’ Fleur smiled mysteriously at her reflection and pulled the dark silk gauze down over her face again. The woman from Take Hat! gaped at her.

‘You’re going to buy them all?’

‘Of course I am. I simply can’t choose between them. They’re all too perfect.’ Fleur turned to the hairdresser. ‘Now, my sweet. Can you come up with something special for my hair which will go under this hat?’ The young man stared back at her and felt a dark pink colour begin to rise up his neck.

‘Oh. Yes. I should think so. I mean…’ But Fleur had already turned away.

‘If you could just put it all onto my hotel bill,’ she was saying to the saleswoman. ‘That’s all right, isn’t it?’

‘Perfectly all right, madam,’ said the saleswoman eagerly. ‘As a guest of the hotel, you’re entitled to a fifteen per cent concession on all our prices.’

‘Whatever,’ said Fleur. She gave a little yawn. ‘As long as it can all go on the bill.’

‘I’ll go and sort it out for you straight away.’

‘Good,’ said Fleur. As the saleswoman hurried out of the room, she turned and gave the young hairdresser a ravishing smile. ‘I’m all yours.’

Her voice was low and melodious and curiously accentless. To the hairdresser’s ears it was now also faintly mocking, and he flushed slightly as he came over to where Fleur was sitting. He stood behind her, gathered together the ends of her hair in one hand and let them fall down in a heavy, red-gold movement.

‘Your hair’s in very good condition,’ he said awkwardly.

‘Isn’t it lovely?’ said Fleur complacently. ‘I’ve always had good hair. And good skin, of course.’ She tilted her head, pushed her hotel robe aside slightly, and rubbed her cheek tenderly against the pale, creamy skin of her shoulder. ‘How old would you say I was?’ she added abruptly.

‘I don’t… I wouldn’t…’ the young man began to flounder.

‘I’m forty,’ she said lazily. She closed her eyes. ‘Forty,’ she repeated, as though meditating. ‘It makes you think, doesn’t it?’

‘You don’t look . . .’ began the hairdresser in awkward politeness. Fleur opened one glinting, pussycat-green eye.

‘I don’t look forty? How old do I look, then?’

The hairdresser stared back at her uncomfortably. He opened his mouth to speak, then closed it again. The truth was, he thought suddenly, that this incredible woman didn’t look any age. She seemed ageless, classless, indefinable. As he met her eyes he felt a thrill run through him; a dart-like conviction that this moment was somehow significant. His hands trembling slightly, he reached for her hair and let it run like slippery flames through his fingers.

‘You look as old as you look,’ he whispered huskily. ‘Numbers don’t come into it.’

‘Sweet,’ said Fleur dismissively. ‘Now, my pet, before you start on my hair, how about ordering me a nice glass of champagne?’

The hairdresser’s fingers drooped in slight dis appointment, and he went obediently over to the telephone. As he dialled, the door opened and the woman from Take Hat! came back in, carrying a pile of hat boxes. ‘Here we are,’ she exclaimed breathlessly. ‘If you could just sign here…’

‘A glass of champagne, please,’ the hairdresser was saying. ‘Room 301.’

‘I was wondering,’ began the saleswoman cautiously to Fleur. ‘You’re quite sure that you want all six hats in black? We do have some other super colours this season.’ She tapped her teeth thoughtfully. ‘There’s a lovely emerald green which would look stunning with your hair…’

‘Black,’ said Fleur decisively. ‘I’m only interested in black.’

***

An hour later, Fleur looked at herself in the mirror, smiled and nodded. She was dressed in a simple black suit which had been cut to fit her figure precisely. Her legs shimmered in sheer black stockings; her feet were unobtrusive in discreet black shoes. Her hair had been smoothed into an exemplary chignon, on which the little black hat sat to perfection.

The only hint of brightness about her figure was a glimpse of salmon-pink silk underneath her jacket. It was Fleur’s rule always to wear some colour no matter how sombre the outfit or the occasion. In a crowd of dispirited black suits, a tiny splash of salmon-pink would draw the eye unconsciously towards her. People would notice her but wouldn’t be quite sure why. Which was just as she liked it.

Still watching her reflection, Fleur pulled the gauzy veil down over her face. The smug expression dis appeared from her face, to be replaced by one of grave, inscrutable sadness. For a few moments she stared silently at herself. She picked up her black leather Osprey bag and held it soberly by her side. She nodded slowly a few times, noticing how the veil cast hazy, mysterious shadows over her pale face.

Then, suddenly, the telephone rang, and she sprang back into life.

‘Hello?’

‘Fleur, where have you been? I have tried to call you.’ The heavy Greek voice was unmistakable. A frown of irritation creased Fleur’s face.

‘Sakis! Sweetheart, I’m in a bit of a hurry…’

‘Where are you going?’

‘Nowhere. Just shopping.’

‘Why do you need to shop? I bought you clothes in Paris.’

‘I know you did, darling. But I wanted to surprise you with something new for this evening.’ Her voice rippled with convincing affection down the phone. ‘Something elegant, sexy . . .’ As she spoke, she had a sudden inspiration. ‘And you know, Sakis,’ she added carefully, ‘I was wondering whether it wouldn’t be a good idea to pay in cash, so that I get a good price. I can draw money out from the hotel, can’t I? On your account?’

‘A certain amount. Up to ten thousand pounds, I think.’

‘I won’t need nearly that much!’ Her voice bubbled over with amusement. ‘I only want one outfit! Five hundred maximum.’

‘And when you have bought it you will return straight to the hotel.’

‘Of course, sweetheart.’

‘There is no of course. This time, Fleur, you must not be late. Do you understand? You-must-not-be-late.’ The words were barked out like a military order and Fleur flinched silently in annoyance. ‘It is quite clear. Leonidas will pick you up at three o’clock. The helicopter will leave at four o’clock. Our guests will arrive at seven o’clock. You must be ready to greet them. I do not want you to be late like last time. It was . . . it was unseemly. Are you listening? Fleur?’

‘Of course I’m listening!’ said Fleur. ‘But there’s someone knocking at the door. I’ll just go and see who it is . . .’ She waited a couple of seconds, then firmly replaced the receiver. A moment later, she picked it up again.

‘Hello? Could you send someone up for my luggage, please?’

Downstairs, the hotel lobby was calm and tranquil. The woman from Take Hat! saw Fleur walking past the boutique, and gave a little wave, but Fleur ignored her.

‘I’d like to check out,’ she said, as soon as she got to the reception desk. ‘And to make a withdrawal of money. The account is in the name of Sakis Papandreous,’

‘Ah, yes.’ The smooth, blond-haired receptionist tapped briefly at her computer, then looked up and smiled at her. ‘How much money would you like?’ Fleur beamed back at her.

‘Ten thousand pounds. And could you order me two taxis?’ The woman looked up in surprise.

‘Two?’

‘One for me, one for my luggage. My luggage is going to Chelsea.’ Fleur lowered her eyes beneath her gauzy veil. ‘I’m going to a memorial service.’

‘Oh dear, I am sorry,’ said the woman, handing Fleur several pages of hotel bill. ‘Someone close to you?’

‘Not yet,’ said Fleur, signing the bill without bothering to check it. She watched as the cashier counted thick wads of money into two crested envelopes, then tenderly took them both, placed them in her Osprey bag and snapped it shut. ‘But you never know.’

***

Richard Favour sat in the front pew of St Anselm’s Church with his eyes closed, listening to the sounds of people filling the church – muted whisperings and shufflings, the tapping of heels on the tiled floor, and ‘Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring’ being played softly on the organ.

He had always hated ‘Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring’; it had been the suggestion of the organist at their meeting three weeks previously, after it had become apparent that Richard could not name a single piece of organ music of which Emily had been particularly fond. There had been a slightly embarrassed silence as Richard vainly racked his brains, then the organist had tactfully murmured. ‘“Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring” is always very popular…’ and Richard had agreed in hasty relief.

Now he gave a dissatisfied frown. Surely he could have thought of something more personal than this turgid, over-popular tune? Emily had certainly been a music-lover, always going to concerts and recitals when her health allowed it. Had she never once turned to him, eyes alight, saying, ‘I love this piece, don’t you?’ He screwed up his eyes and tried to remember. But the only vision that came to him was of Emily lying in bed, eyes dulled, wan and frail and uncomplaining. A spasm of guilty regret went through him. Why had he never asked his wife what her favourite piece of music was? In thirty-three years of marriage, he had never asked her. And now it was too late. Now he would never know.

He rubbed his forehead wearily, and looked down at the engraved order of service on his lap. The words stared back up at him. Service of Memorial and Thanksgiving for the life of Emily Millicent Favour. Simple black lettering, plain white card. He had resisted all attempts by the printers to introduce such prized features as silver borders or embossed angels. Of that, he thought, Emily would have approved. At least… he hoped she would.

It had taken Richard several years of marriage to Emily to realize that he didn’t know her very well, and several more for him to realize that he never would. At the beginning, her serene remoteness had been part of her appeal, along with her pale, pretty face and the neat, boyish figure which she kept as resolutely hidden as she did her innermost thoughts. The more she had kept herself hidden, the more tantalized Richard had become; he had approached their wedding day with a longing bordering on desperation. At last, he had thought, he and Emily would be able to reveal their secret selves to each other. He had yearned to explore not only her body but her mind, her person; to discover her most intimate fears and dreams; to become her lifelong soulmate.

They’d been married on a bright, blustery day, in a little village in Kent. Emily had looked composed and serene throughout; Richard had supposed she was simply better than him at concealing the nervous anticipation that surely burned as intensely within her as it did in him – an anticipation which had become stronger as the day was swallowed up and the beginning of their life together drew near.

Now he closed his eyes, and remembered those first, tingling seconds, as the door had shut behind the porter and he was alone with his wife for the first time in their Eastbourne hotel suite. He’d gazed at her as she took off her hat with the smooth, precise movements she always made, half-longing for her to throw the silly thing down and rush into his arms, and half-longing for this delicious, uncertain waiting to last for ever. It had seemed that Emily was deliberately delaying the moment of their coming together; teasing him with her cool, oblivious manner, as though she knew exactly what was going through his mind.

And then, finally, she’d turned, and met his eye. And he’d taken a breath, not knowing quite where to start; which of his pent-up thoughts to release first. And she’d looked straight at him with remote blue eyes and said, ‘What time is dinner?’

Even then, he’d thought she was still teasing. He’d thought she was purposely prolonging the sense of anticipation, that she was deliberately stoppering up her emotions until they became too overwhelming to control, when they would flood out in a huge gush to meet and mix with his. And so, patiently, awed by her apparent self-control, he’d waited. Waited for the gush; the breaking of the waters; the tears and the surrender.

But it had never happened. Emily’s love for him had never manifested itself in anything more than a slow drip-drip of fond affection; she’d responded to his every caress, his every confidence, with the same degree of lukewarm interest. When he tried to spark a more powerful reaction in her, he’d been met first by in comprehension, then, as he grew more strident, by an almost frightened resistance.

Eventually he’d given up trying. And gradually, almost without his realizing, his own love for her had begun to change in character. Over the years, his emotions had stopped pounding at the surface of his soul like a hot, wet tidal wave and had receded and solidified into something firm and dry and sensible. And Richard, too, had become firm and dry and sensible. He’d learned to keep his own counsel, to gather his thoughts dispassionately and say only half of what he was really thinking. He’d learned to smile when he wanted to beam, to click his tongue when he wanted to scream in frustration; to restrain himself and his foolish thoughts as much as possible.

Now, waiting for her memorial service to begin, he blessed Emily for those lessons in self-restraint. Because if it hadn’t been for his ability to keep himself in check, the hot, sentimental tears which bubbled at the back of his eyes would now have been coursing uncontrollably down his cheeks, and the hands which calmly held his order of service would have been clasped over his contorted face, and he would have been swept away by a desperate, immoderate grief.

The church was almost full when Fleur arrived. She stood at the back for a few moments, surveying the faces and clothes and voices in front of her; assessing the quality of the flower arrangements; checking the pews for anyone who might look up and recognize her.

But the people in front of her were an anonymous bunch. Men in dull suits; ladies in uninspired hats. A flicker of doubt crossed Fleur’s mind. Could Johnny have got this one wrong? Was there really any money lurking in this colourless crowd?

‘Would you like an order of service?’ She looked up to see a long-legged man striding across the marble floor towards her. ‘It’s about to start,’ he added with a frown.

‘Of course,’ murmured Fleur. She held out her pale. scented hand. ‘Fleur Daxeny. I’m so glad to meet you… Sorry, I’ve forgotten your name…’

‘Lambert.’

‘Lambert. Of course. I remember now.’ She paused, and glanced up at his face, still wearing an arrogant frown. ‘You’re the clever one.’

‘I suppose you could say that,’ said Lambert, shrugging.

Clever or sexy, thought Fleur. All men want to be one or the other – or both. She looked at Lambert again. His features looked overblown and rubbery, so that even in repose he seemed to be pulling a face. Better just leave it at clever, she thought.

‘Well, I’d better sit down,’ she said. ‘I expect I’ll see you later.’

‘There’s plenty of room at the back,’ Lambert called after her. But Fleur appeared not to hear him. Studying her order of service with an absorbed, solemn expression, she made her way quickly to the front of the church.

‘I’m sorry,’ she said, pausing by the third row from the front. ‘Is there any room? It’s a bit crowded at the back.’

She stood impassively while the ten people filling the row huffed and shuffled themselves along; then, with one elegant movement, took her place. She bowed her head for a moment, then looked up with a stern, brave expression.

‘Poor Emily,’ she said. ‘Poor sweet Emily.’

‘Who was that?’ whispered Philippa Chester as her husband returned to his seat beside her.

‘I don’t know,’ said Lambert. ‘One of your mother’s friends, I suppose. She seemed to know all about me.’

‘I don’t think I remember her,’ said Philippa. ‘What’s her name?’

‘Fleur. Fleur something.’

‘Fleur. I’ve never heard of her.’

‘Maybe they were at school together or something.’

‘Oh yes,’ said Philippa. ‘That could be it. Like that other one. Joan. Do you remember? The one who came to visit out of the blue?’

‘No,’ said Lambert.

‘Yes you do. Joan. She gave Mummy that hideous glass bowl.’ Philippa squinted at Fleur again. ‘Except this one looks too young. I like her hat. I wish I could wear little hats like that. But my head’s too big. Or my hair isn’t right. Or something.’

She tailed off. Lambert was staring down at a piece of paper and muttering. Philippa looked around the church again. So many people. All here for Mummy. It almost made her want to cry.

‘Does my hat look all right?’ she said suddenly.

‘It looks great,’ said Lambert without looking up.

‘It cost a bomb. I couldn’t believe how much it cost. But then, when I put it on this morning, I thought…’

‘Philippa!’ hissed Lambert. ‘Can you shut up? I’ve got my reading to think about!’

‘Oh yes. Yes, of course you have.’

Philippa looked down, chastened. And once again she felt a little pinprick of hurt. No-one had asked her to do a reading. Lambert was doing one, and so was her little brother Antony, but all she had to do was sit still in her hat. And she couldn’t even do that very well.

‘When I die,’ she said suddenly, ‘I want everyone to do a reading at my memorial service. You, and Antony, and Gillian, and all our children…’

‘If we have any,’ said Lambert, not looking up.

‘If we have any,’ echoed Philippa morosely. She looked around at the sea of black hats. ‘I might die before we have any children, mightn’t I? I mean, we don’t know when we’re going to die, do we? I could die tomorrow.’ She broke off, overcome by the thought of herself in a coffin, looking pale and waxy and romantic, surrounded by weeping mourners. Her eyes began to prickle. ‘I could die tomorrow. And then it would be…’

‘Shut up,’ said Lambert, putting away his piece of paper. He stretched his hand down out of sight and casually pinched Philippa’s fleshy calf. ‘You’re talking rubbish,’ he murmured. ‘What are you talking?’

Philippa was silent. Lambert’s fingers gradually tightened on her skin, until suddenly they nipped so viciously that she gave a sharp intake of breath.

‘I’m talking rubbish,’ she said, in a quick, low voice.

‘Good girl,’ said Lambert. He released his fingers. ‘Now, sit up straight and get a grip.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Philippa breathlessly. ‘It’s just a bit… overwhelming. There are so many people here. I didn’t know Mummy had all these friends.’

‘Your mother was a very popular lady,’ said Lambert. ‘Everyone loved her.’

And no-one loves me, Philippa felt like saying. But instead, she prodded helplessly at her hat and tugged a few locks of wispy hair out from under the severe black brim, so that by the time she stood up for the first hymn, she looked even worse than before.